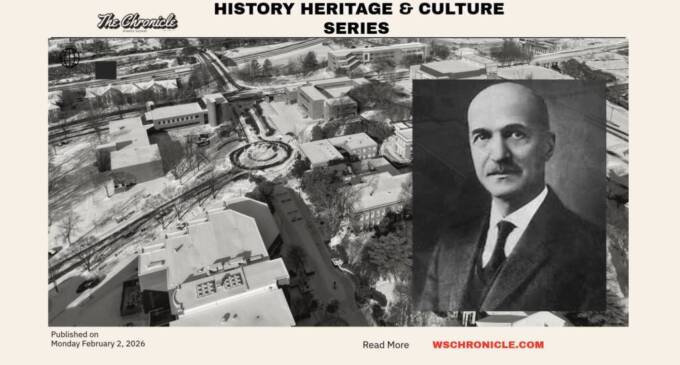

One room. One teacher. Twenty-five students – Part 1 | History Heritage & Culture Series

By Derwin L. Montgomery

The Winston-Salem Chronicle

One Room. One Teacher. Twenty-Five Students

That’s how the institution that would become Winston-Salem State University began—founded on September 28, 1892, as Slater Industrial Academy. But from the beginning, its founder, Simon Green Atkins, envisioned something larger than a school. He imagined an ecosystem—one that joined education, housing, civic life, and moral formation into a single project aimed at the full flourishing of African Americans in a South still reeling from the collapse of Reconstruction.

Atkins was not simply responding to an educational gap. He was responding to a structural reality: Black progress would not come from classrooms alone. It would require stable homes, healthy communities, economic opportunity, and institutions capable of outlasting their founders. Slater Industrial Academy—later Slater Normal School, Winston-Salem Teachers College, and eventually Winston-Salem State University—was built to serve the whole person so that African Americans could build sustainable lives in a society structured against them.

A Founder Shaped by Purpose, Not Accident

Born in 1862 in Haywood County, North Carolina, Atkins came of age during the fragile promise of Reconstruction and the tightening grip of Jim Crow. He graduated from St. Augustine’s College in 1884 and went on to work at Livingstone College, where he led the grammar school department and later served as treasurer. Long before founding Slater, Atkins spent summers traveling across North Carolina conducting teacher institutes for Black educators. These experiences convinced him of a hard truth: the greatest educational need in Black communities was not simply access to schooling, but the preparation of teachers who could multiply learning across generations.

When Atkins arrived in Winston in the early 1890s as principal of the city’s public school for Black students, he quickly recognized both the need and the opportunity. The Black population of Winston was growing, yet educational options were limited, underfunded, and precarious. Rather than waiting for the state to act, Atkins did what he would do repeatedly throughout his career—he built.

In January 1891, he appeared before Winston’s Board of Trade seeking support for a new educational institution for African Americans. This moment is revealing. Atkins did not appeal only to moral duty; he appealed to civic self-interest. Education, he argued implicitly, was foundational to the city’s stability, workforce, and future. From the beginning, Slater Industrial Academy was conceived not as a marginal charity but as a civic asset.

Education as Service, Not Escape

Atkins rejected the idea that education was merely a ladder out of Black communities. For him, education was a tool of service—something that strengthened families, neighborhoods, and civic life.

In one of his most revealing statements, Atkins wrote:

“We want to educate the people for service rather than for success. We are not opposed to industrial education… We believe the Negro’s industrial opportunity… is very great… Let him be made a man, and everything else will take care of itself.”

This philosophy placed him in dialogue with—yet distinct from—figures like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Atkins embraced industrial education, but not as a ceiling. He insisted that vocational skill, moral development, and intellectual formation belonged together. Education was not about producing laborers alone; it was about producing citizens.

That conviction shaped Slater’s early curriculum, which combined teacher preparation, industrial training, and character formation. By the mid-1890s, the school had evolved into Slater Normal and Industrial School, explicitly emphasizing teacher training as its central mission. Atkins understood that teachers were force multipliers: one trained educator could shape hundreds of lives over a career.

Naming, Philanthropy, and Strategic Reality

The name “Slater” reflected both gratitude and strategy. The school drew support from the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen, a national philanthropic effort dedicated to advancing Black education in the post-Civil War South, particularly through normal (teacher-training) and industrial schools.

Like many historically Black colleges and universities, Slater navigated a funding landscape shaped by white philanthropy. Institutions such as Spelman, Morehouse, Fisk, and Claflin carried names tied to benefactors and mission boards. Yet the presence of philanthropic names should not obscure the reality that Black leadership, Black labor, and Black community investment made these schools function.

At Slater, Black citizens raised significant funds locally, while philanthropic contributions supplemented—rather than replaced—community commitment. Atkins himself articulated a pragmatic understanding of this reality. In an 1899 letter, he wrote:

“It is impossible for the colored people of the State to be elevated except with the aid and good will of their white neighbors.”

This was not submission; it was strategy. Atkins understood the constraints of his era and worked within them without surrendering Black agency.

The Columbian Exposition and a Vision for Place

Atkins’ philosophy of education extended beyond classrooms into the built environment. After visiting the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago—a massive showcase of urban planning, architecture, and civic imagination—Atkins returned to Winston with renewed clarity about the role of place in shaping people.

The Exposition’s “White City” symbolized order, beauty, and coordinated civic life. While African Americans were largely excluded from its official narrative, Atkins drew inspiration from its underlying premise: environment matters.

When developers proposed naming a new Black neighborhood after him, Atkins declined. Instead, he suggested Columbia Heights, honoring the exposition that had stirred his imagination. The name itself was aspirational—a declaration that Black residents deserved dignity, beauty, and permanence.

Housing as Educational Infrastructure

Columbia Heights was not a side project. It was central to Atkins’ educational strategy.

Atkins recognized a critical obstacle to Slater’s success: attracting and retaining professionally trained teachers. Qualified educators—especially those with families—would not live in overcrowded, unhealthy rental districts imposed on Black residents. If Slater was to thrive, its teachers needed stable homes, safe streets, and a sense of ownership.

Historic records describe Atkins’ reasoning plainly: the success of the school depended on creating a nearby Black community where residents could own their homes. Working with civic leaders and land developers, Atkins helped facilitate the creation of Columbia Heights adjacent to the campus. He and his family were among its first residents.

The neighborhood quickly became home to Black professionals—teachers, ministers, doctors, lawyers, skilled craftsmen—forming a middle-class enclave rooted in education and mutual support. Housing stability reinforced educational stability. Teachers stayed. Families invested. The school gained legitimacy.

In a letter to Alexander Purvis of Hampton Institute, now Hampton University, Atkins distilled this belief into a striking sentence:

“He who helps the colored people to a footing in the soil helps them most.”

Homeownership, for Atkins, was not merely economic—it was moral, civic, and educational.

Teaching the Whole Person

Atkins’ educational philosophy emphasized character as much as curriculum. His personal motto—often repeated to students—was simple and demanding:

“Self-support, self-respect, and self-defense.”

These were not abstract ideals. Self-support meant economic independence. Self-respect meant dignity in a society determined to deny it. Self-defense meant the intellectual and moral capacity to withstand injustice without internalizing inferiority.

He believed deeply in what he called the “sanative and stabilizing influence of home life,” viewing homes as cultural centers that shaped values, aspirations, and civic responsibility. Education, housing, and moral formation were inseparable threads in the same fabric.

Community Impact and Civic Recognition

Atkins’ work did not go unnoticed. White and Black civic leaders alike acknowledged the institution he was building.

H.E. Fries, chairman of Slater’s board of trustees, credited Atkins with producing “particularly efficient teachers,” noting that graduates became “honest business and professionals” who cooperated “in every civic project” aimed at improving the community.

Check back on Thursday for Part 2.

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment