Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr., civil rights leader with deep North Carolina ties, dies at 84

By. Derwin Montgomery

The Winston-Salem Chronicle

Winston-Salem and communities across North Carolina are remembering Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. not only as a national civil rights figure and two-time presidential candidate, but as a leader whose roots and influence ran deep through the state’s campuses, churches and political halls.

Jackson, who died this week at 84, built part of his foundation in North Carolina — first as a student activist and later as a presidential contender who drew thousands to Winston-Salem State University during his historic 1988 campaign.

Born in Greenville, South Carolina, Jackson transferred to North Carolina A&T State University in 1960. At A&T, a historically Black university in Greensboro already nationally recognized for the 1960 sit-in movement, Jackson emerged as a student leader. He served as student government president and quarterback of the football team, while organizing and leading demonstrations against segregation and racial discrimination.

It was at A&T where Jackson met Jacqueline L.B. Jackson, his future wife and lifelong partner in civil rights advocacy. The couple married in 1962.

North Carolina shaped Jackson’s early political voice. In 1988, when he launched his second bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, Jackson announced his campaign in Raleigh — signaling the South, and Black voters in particular, as central to his national coalition.

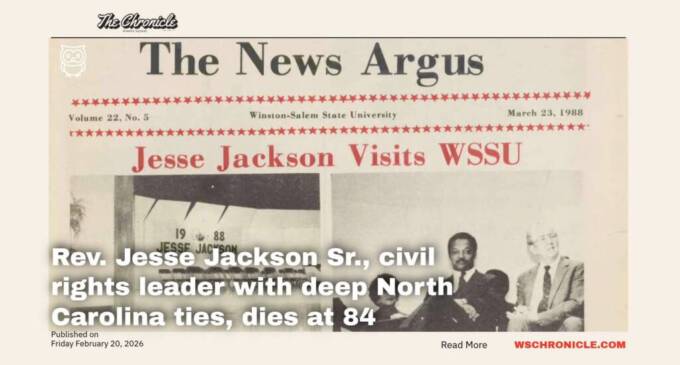

Later that spring, Winston-Salem State University hosted Jackson as part of his campaign swing through the state. The campus newspaper at the time, The News Argus, documented his visit under the headline “Jesse Jackson Visits WSSU,” describing packed venues and enthusiastic student crowds. According to contemporaneous accounts, “screaming students and supporters” filled the university’s spaces as Jackson spoke about voting rights, economic justice and expanded political participation.

His 1988 campaign made history. Jackson won several state primaries and caucuses and finished second overall in the Democratic delegate count — the strongest showing by an African American presidential candidate to that date. His “Rainbow Coalition” platform emphasized racial equity, workers’ rights, expanded access to education and voting protections — issues that resonated strongly in North Carolina’s urban centers and historically Black colleges and universities.

Jackson’s ties to Winston-Salem extended beyond campaign stops. Over the decades, he worked alongside clergy, civil rights leaders and elected officials across the state, including faith leaders in Forsyth County and advocates engaged in voting rights, economic opportunity and education equity.

For many in Winston-Salem — particularly in East Winston and among HBCU alumni — Jackson’s visits represented more than political theater. They symbolized national recognition of local Black institutions and communities that have long carried the burden of organizing for equity.

Jackson rose to national prominence as a close associate of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., serving as a leader in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference before founding Operation PUSH and later the Rainbow Coalition. His career spanned more than five decades, blending electoral politics, corporate accountability campaigns, voter registration drives and international diplomacy efforts.

In North Carolina, his presence often bridged generations — from students engaged in campus activism to seasoned clergy who viewed him as part of the extended King-era movement.

Political scientists have long noted that Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 campaigns helped expand Black voter participation in Southern states, including North Carolina, laying groundwork that reshaped Democratic Party politics in the region.

His legacy, observers say, is both national and local.

“He made young people believe they belonged in the political process,” several former North Carolina organizers have said in past reflections about his visits to the state’s HBCUs.

Jackson publicly disclosed in 2017 that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. In recent years, he stepped back from public life.

As North Carolina reflects on his passing, civic leaders and clergy are expected to hold memorial services and tributes in the coming days. Local universities and faith communities are also planning remembrances.

For Winston-Salem, Jackson’s legacy is preserved not only in national headlines but in archival photographs, campus newspapers and the memories of students who once packed auditoriums to hear a message that linked Greensboro sit-ins, Raleigh campaign launches and East Winston aspirations into a single call for justice.

His life traced a path from Southern campuses to the national stage — and back again.

Funeral arrangements have not yet been publicly detailed.

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment