Neurosurgeon blazes a trail for others to follow

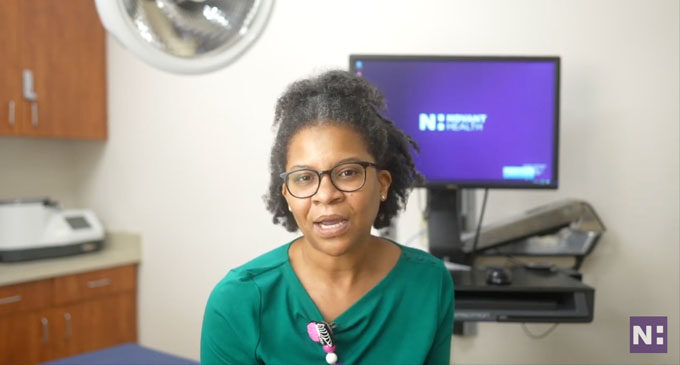

Dr. Michaux Kilpatrick

Dr. Michaux Kilpatrick is 1 of only 33 Black female neurosurgeons in the U.S.

By Andrea Cooper

Dr. Michaux Kilpatrick could have made a fine crime scene investigator. As a girl, she enjoyed watching Quincy, a late 1970’s TV show about a medical examiner. “I loved that he would go to different scenes, figure out what happened and solve the crime before anyone else,” she recalled.

The prospect of a career with blood and guts as central characters didn’t faze Kilpatrick. She imagined herself analyzing evidence in the field, performing autopsies in the lab and probing medical mysteries.

That is, until she discovered a new setting for her investigative powers. Fast-forward to medical school where she took a neurosurgery elective and realized she was thrilled to solve medical puzzles in the operating room.

Today, Michaux (pronounced “Misha”) Kilpatrick is a neurosurgeon at Novant Health Brain & Spine Surgery in Kernersville, with satellite offices in Thomasville and Greensboro. She treats medical ailments involving the brain, spinal cord or peripheral nerves – the nerves in the arms and legs – that may be improved or resolved with surgery. Her cases range from pinched nerves and ruptured discs to brain tumors. Neurologists, in comparison, also treat diseases of the nervous system, but focus on nonsurgical treatments.

In a field dominated by white males, Kilpatrick is a profound exception. There are only 33 Black female neurosurgeons in the U.S., comprising 0.6% of the neurosurgical workforce, according to the journal World Neurology. Kilpatrick is one of them. She earned her medical degree simultaneously with a doctorate in neurobiology at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Training to be a neurosurgeon is a long haul. After medical school, the typical neurosurgery residency lasts six or seven years. Kilpatrick credits UNC for providing a welcoming environment for female neurosurgeons. The chief resident when she joined the program was a woman, and at one point, about half the residents were women. Kilpatrick believes it will take that level of representation and accessibility to attract other women into the field.

Kilpatrick grew up with a trailblazer. Her dad, Dr. George R. Kilpatrick Jr., was the first African American pulmonologist in North Carolina. A physician in the military, he was stationed in Korea when Kilpatrick was born in Chapel Hill. The family, including her big sister and her mom, who worked as a teacher, moved around to Denver, Colo., and El Paso, Texas, before returning to Greensboro. Her dad still maintains a practice there.

Kilpatrick didn’t plan to become a physician when she headed to Hampton University in Virginia, where she majored in chemistry and minored in psychology. The minor required her to take neurobiology courses. “It was that early exposure to the neurosciences that first got me interested,” she said. She toyed with earning a doctorate so she could pursue investigative research and maybe fulfill a version of that childhood dream.

An advisor suggested she consider medical school. During a summer pre-med program, she was assigned to a neurosurgeon who was also a researcher. “He would see patients and go to the operating room, and then come back to his lab and do medical research.” The combination intrigued Kilpatrick.

She ultimately pursued an MD-Ph.D., an eight-year program as demanding as it sounds. It included four years in the lab, conducting graduate-level research. “We were implanting little electrodes into the brains of rodents and monitoring the different chemicals that get released during different activities,” she explained. “That was fascinating to me.”

Ultimately, her neurosurgery elective in medical school led to her niche in the operating room. “There’s a culture in the OR that’s unique to the OR,” she said. “I find you’re either drawn to it or repelled by it.” She was all-in.

Following graduation, Ewend hired her as a resident at UNC Health. Ewend said, from the beginning, Kilpatrick was poised and unflappable, though the residency “was very stressful, a mile a minute. She moved through that working very hard and making it look effortless, although clearly it was not.” He later hired Kilpatrick for a position at High Point Medical Center, then part of the UNC Hospital system.

Kilpatrick brings a variety of strengths to the work. It’s tempting to think of neurosurgery as a technical task like cracking a safe, all based on incredibly precise movement, Ewend said. “But so much of it is about judgment and knowing what’s around corners,” he said. He saw Kilpatrick making wise decisions and getting terrific outcomes for her patients, “not just because she could move her hands skillfully, but because she was very thoughtful about what she did.”

Kilpatrick is not one to remark on her pioneering status unless prompted. Even then, it’s in low-key fashion.

“I don’t know that it’s weighing on me, mainly because I don’t think about it,” she said. “What’s always been in the forefront of my mind is to do my best, and to do my best for my patients. I’m not thinking as much about myself. When you’re thinking about others, and maybe not focusing so much on what you’re going through in the moment, it actually can make things easier for you.”

To help the next generation of women move forward, she mentors female pre-med students at N.C. A&T and invites them to her office to shadow her on the job.

Her colleagues love her daily vibe. The OR is easily the mostly tightly wound corner of any hospital, yet Kilpatrick has a reputation for putting people at ease in high-stress settings. As she prepped for surgery on a recent morning at Novant Health Kernersville Medical Center, one nurse explained: “This is a direct environment where people work quickly without a lot of ‘please and thank you,’ but she makes you feel comfortable” and keeps the room on an even keel. Her OR music of choice? Bruno Mars.

With her credentials, she could probably practice wherever she likes. But North Carolina is home for her, her husband, Brent Moore, an investment banker, their twin 11-year-old girls, and Kilpatrick’s parents. “If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a whole urban city to raise twins,” she quipped. She’s grateful that “Mama Kay” and “Pops” pick up the girls at school and host sleepovers over the weekend from time to time.

The girls understand the value of what their mother does. “On nights when they ask, ‘Mommy, are you going in to do surgery?’ and I say ‘Yes,’ that’s OK. They know mommy’s going in to help somebody.”

Kilpatrick considers family and faith both foundational to her life. She also volunteers with Old North State Medical Society, one of the oldest African American medical societies in the country. The group has provided COVID-19 vaccine clinics and testing.

For Kilpatrick’s patients, surgery is a tool that can lead to better health. Kilpatrick finds surgery deeply meaningful and satisfying for that reason. “You can have a person who is suffering, and you can provide an intervention that totally changes their life for the better in a relatively short period of time,” she said.

That’s why she said she’s happy when a patient tells her, “Thanks, Dr. Kilpatrick. You’ve been great. But I’m glad I don’t need to see you anymore.”