Experiencing a bit of what released offenders go through

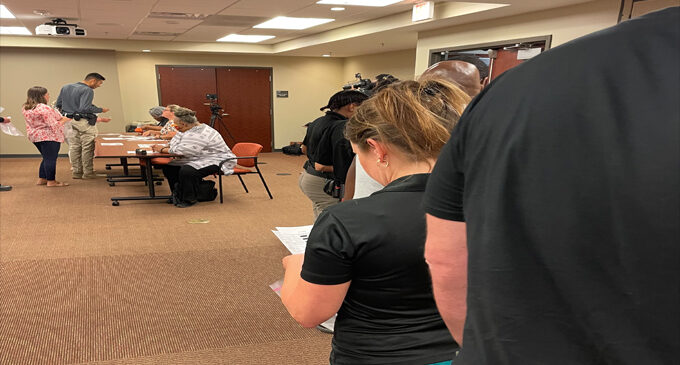

Participants in the Aug. 16 reentry simulation endured long lines, much like those released offenders go through daily.

By John Railey

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb in his skin and walk around in it.”

— Atticus Finch in “To Kill a Mockingbird”

I’ve just been released from prison. Chaos and frustration consume my days as I wait in long lines to get a state identification card, see my probation officer and try to find work, the whole time relying on an inefficient public transportation system to get around. And if I don’t make it back to my halfway house by curfew, I face a return to prison.

I was used to being told what to do in prison. Now I have to figure it all out on my own, often on the internet, which I’ve grown rusty on.

That’s the world I got a glimpse of on Aug. 16 when I took part in a reentry simulation at the Forsyth County Sheriff’s Office. With more than 50 others – including law-enforcement officers and social service workers – I spent a morning racing around a large room, bouncing back and forth from one table set up as a probation office, to another set up as a drug treatment center, to still another set up as a halfway house. Before that day, I had some idea of what released offenders go through from interviewing them for my job at Winston-Salem State University’s Center for the Study of Economic Mobility (CSEM), where reentry is a research bedrock. But the simulation gave me a real handle on what released offenders encounter.

Getting out of prison is hard and frustrating. Every complex turn is challenging and can lead to failure – a return to prison that is costly in financial and human terms. “Many of these men and women are so barren of role models and mentors,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Rob Lang of Winston-Salem told me recently. “They lack internet skills. Some can hardly read, or have reading deficits. Some don’t have any food and are hungry. They need a little help.”

Lang’s job as a prosecutor involves sending those convicted of crimes to prison. But he has long realized released offenders need a path back, and has worked toward that as the Project Safe Neighborhoods and Reentry coordinator for his office. That effort continues with the reentry simulations. Lang’s office partners with Rebecca Sauter’s Project Reentry, which she leads, and along with other community partners on the simulations to help those who work with released offenders – or want to do that work – better understand the maze released offenders confront.

These events are sorely needed.

Reentry work is a bedrock for CSEM, which realizes the heavy financial and human costs of recidivism. Douglas Bates, a CSEM Research Fellow and assistant professor in WSSU’s Department of Social Work, is developing a survey that will help employers and released offenders better adjust to the workplace. Among CSEM’s partner organizations are the Do School, whose participants can include released offenders learning the construction trade, and Project M.O.O.R.E., which helps at-risk youth and is run by David Moore, who did time in prison decades ago before turning his life around.

CSEM’s Associate Director, Alvin Atkinson, worked with Lang on reentry efforts when Atkinson was with WSSU’s Center for Community Safety in the early 2000s.

The simulation events are part of a nationwide initiative and is the latest of several to be held in our state and area. Participants, taking on the roles of released offenders, deal with challenges of medical care, mental health, substance abuse, child support and employment. “We create different scenarios,” Lang said. “This is modeled on real-life experiences and barriers that these guys have. We show the chaos.”

Transportation is another big challenge. “Over and over, transportation is one of the biggest barriers,” Lang said. For example, he said, a released offender lacking a driver’s license might depend on a coworker to get to his job. But the coworker loses his job, and the released offender relies on cabs to get to work. “So he’s spending $18 to get to an $8-an-hour job,” Lang said.

CSEM’s research has documented similar challenges among those in the general population, including the fact that riders who use city buses to get to work spend an average of 12 hours a week on buses, helping to lead The Winston-Salem Foundation and Forsyth Technical Community College to tackle the issue. Reform of the public transportation system can especially help released offenders. In other areas of the state, Lang said, a factory, realizing problems with public transportation, started shuttle services for released offenders, and a city tweaked its bus lines to help them get to work. In Forsyth County, Lang encourages released offenders to use the driver’s license restoration project offered by the district attorney’s office.

The released offenders often turn out to be good workers, Lang said. “They’re motivated by not wanting to go back.”

Project Reentry is making a difference. The statewide recidivism rate is 32%, according to Project Reentry, but for released offenders who take part in their programs, that rate is 10.7%.

The reentry simulation events can help. “People who have been through the system talk about who helped them and how,” Lang said, and participants learn how to better help released offenders, including through enhanced coordination among everyone from probation officers to food bank operators.

“We can do our jobs better,” Lang said. “Many released offenders do want to change, if we can just help a little bit.”

John Railey (raileyjb@gmail.com) is the writer-in-residence for Center for the Study of Economic Mobility, www.wssu.edu/csem.