From Slater to the City | Part 2 | History Heritage & Culture Series

By Derwin L. Montgomery

The Winston-Salem Chronicle

One room. One teacher. Twenty-five students – Part 1 | History Heritage & Culture Series

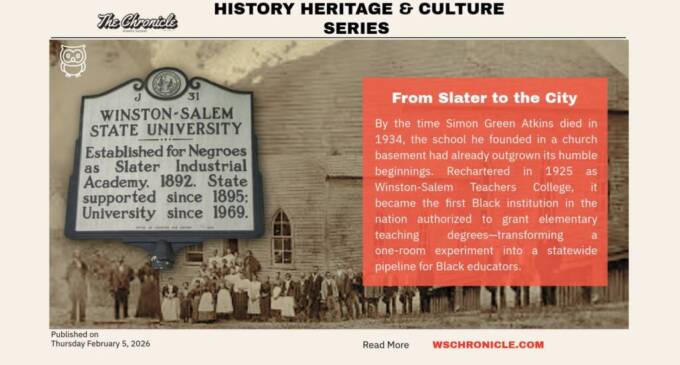

Following Atkins’ death in 1934, the Winston-Salem Journal reflected on the school’s humble beginnings—initially operating in the basement of a church—and praised his wisdom, persistence, and ability to build enduring institutions with limited resources.

By that time, Slater had already begun its transformation into a state-recognized teachers college. In 1925, it was rechartered as Winston-Salem Teachers College, becoming the first Black institution in the nation authorized to grant degrees for teaching in the elementary grades. What began as one room had become a pipeline for professional Black educators across North Carolina.

A Legacy That Outlived Its Founder

Atkins retired in 1930, leaving behind more than buildings. He left a model—one that insisted education must be embedded in community, rooted in dignity, and oriented toward service.

The institution he founded would continue to evolve, becoming Winston-Salem State University, a comprehensive public university educating thousands of students across disciplines. Yet its founding DNA remains visible: a commitment to access, to teacher preparation, to community engagement, and to the belief that education is most powerful when it addresses the whole person.

Simon Green Atkins did not simply found a school. He built a vision of Black advancement that refused to separate learning from living. In an era that offered African Americans little security and fewer guarantees, he constructed something rare—an institution designed not only to teach people how to make a living, but how to build lives.

More than a century later, that vision still stands.

Why Atkins’ Vision Matters in Winston-Salem Right Now

If Simon Green Atkins were walking the streets today, he would recognize something we sometimes try to treat as separate: housing and education are still linked, and stability is still a prerequisite for success.

In the early days of Slater, Atkins saw that education could not be sustained if people were living in conditions that undermined learning, health, and the ability to plan for the future. That insight was not theoretical. It was pragmatic. It was also prophetic. He looked at the lives of African Americans in a city growing around them and understood that schools do not thrive when communities are unstable—and communities do not stabilize when families lack safe, affordable places to live.

That connection feels especially urgent now because the city’s housing challenge is no longer a quiet concern—it is a defining pressure shaping who can remain in Winston-Salem, who can build wealth, and whose children can experience consistent schooling. A long-cited local study found a shortage of about 16,000 affordable homes in Winston-Salem, and local officials have said the gap is likely larger now than it was before the pandemic. When families are spending too much of their income on rent, or moving frequently because of rising costs, education becomes harder—not because people don’t care, but because daily life becomes triage.

That reality mirrors the world Atkins confronted: not the same policies, not the same legal order, but the same spiritual question—what does it take for Black families to have a fair chance to flourish? Atkins’ answer wasn’t only “build a school.” It was “build the conditions a school needs.”

In modern language, Atkins was doing what we now call community development—and Winston-Salem State University has, at key moments, returned to that founding posture.

A Modern Return to the Founder’s Blueprint

One of the clearest examples is the S.G. Atkins Community Development Corporation, which was established by Winston-Salem State University in 1998 to stabilize and improve conditions in the census tracts surrounding campus—areas that include Columbia Heights, East Winston, and Claremont. A federal HUD case study describes the university’s move in that period as part of a mission to forge a “progressive response to the needs of society,” connecting the institution’s identity to the conditions of the neighborhoods around it.

This was not just a program—it was, in many ways, a turn back toward Atkins’ original belief that the university’s purpose includes the whole person and the whole community. This matters historically because it shows the institution, more than a century after Slater’s founding, intentionally re-engaging the founder’s logic: education and neighborhood conditions rise and fall together.

And the CDC’s work has remained rooted in that integrated approach—promoting homeownership, development, job creation, and community-centered revitalization around the campus.

What Winston-Salem Can Learn From Atkins Now

Atkins’ model challenges Winston-Salem to stop treating housing as a standalone issue or a “later” issue. In his worldview, housing was not merely shelter; it was infrastructure for learning, workforce stability, and dignity. That is why Columbia Heights was not cosmetic. It was strategic—built to create a stable environment that could attract teachers, retain talent, and cultivate a Black professional ecosystem alongside the school.

That is also why the city’s current housing limitations should be discussed not only in the language of markets and supply, but in the language of opportunity and human development. When a city cannot produce enough homes at prices working people can afford, it constricts educational outcomes, workforce readiness, public health, and generational mobility—especially for communities that have historically been blocked from wealth-building.

In that sense, the argument isn’t simply that Winston-Salem should admire Simon Green Atkins. It is that Winston-Salem needs more of him—more of the leadership posture that refuses to separate education from living conditions, more of the civic imagination that treats neighborhoods as part of the educational mission, and more of the institutional courage to invest in the conditions that make human flourishing possible.

Atkins built a school. But just as importantly, he built a theory of success—one that insisted African Americans deserved not only instruction, but stability, dignity, community, and the tools to endure. That vision is not trapped in the past. It’s a blueprint still waiting to be fully practiced in the present.