Malinda Russell publishes first cookbook by a Black author in 1866

By David Winship

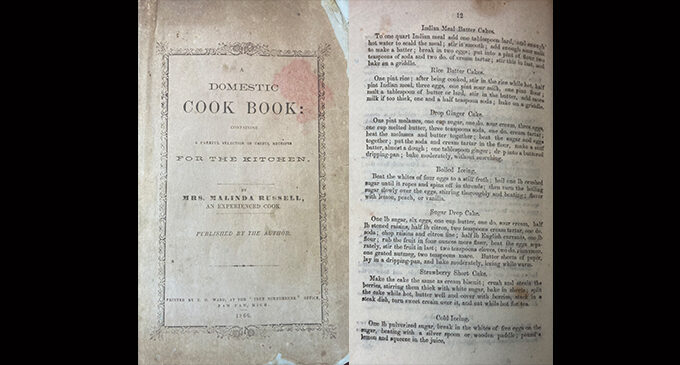

Malinda Russell was a culinary pioneer in the middle of the nineteenth century, whose “A Domestic Cook Book” was the first cookbook authored by an African American woman in the United States. It was printed in Paw Paw, Michigan, in 1866. Its story is a look at the heritage and history of the years leading up to and encompassing the Civil War from the perspective of a free woman of color. In the book’s introduction, she says, “I have put out this book with the intention of benefiting the public as well as myself.”

The cookbook contains 260 recipes, which were spelled “receipts” throughout the book. Russell’s cooking career spanned over 25 years, cooking for households and operating a bakery. The cookbook was discovered by culinary historian Janice Longone in the late twentieth century and it was reprinted the first time in 2007. It has recently been reprinted in 2025 by the University of Michigan Regional Press. It is available on Amazon, but is currently sold out. It can be downloaded free on Kindle.

Malinda Russell was a determined woman.

She was a free woman because her grandmother had been emancipated in Virginia. According to Virginia law before the Civil War, if slaves were emancipated, they had to move out of the state. Malinda was born in Washington County, Tennessee, around 1830 and grew up in Greenville, Tennessee.

She traveled a great deal during her first 40 years, from Greeneville to Lynchburg and Abingdon, Virginia, and back to the countryside outside Greeneville. Before the Civil War, she attempted to emigrate to Liberia, having saved enough money for her passage. However, she was robbed by fellow emigrees, and she had to start all over again. She re-settled in Lynchburg, Virginia, where she cooked and traveled with white ladies as a personal nurse. An endorsement of her character was included in her brief description of her life.

About 1850 she married Anderson Vaughan in Virginia. After leaving Lynchburg, she operated a laundry business in Abingdon, Virginia, in the years between 1851-1855 where “Malinda Vaughan, Fashionable Laundress, would respectfully inform the Ladies and Gentlemen of Abingdon, that she is prepared to wash and iron every description of clothing in the neatest and most satisfactory matter.” She had a son, disabled with a malformed hand, who she cared for all her life.

After her husband died, she returned to the Greenville, Tennessee, area, where she first operated a boarding house for three years, then she had a bakery business for six years during the Civil War. There was Union support in East Tennessee and Malinda Russell heard of the “Garden of the West,” Michigan. Under a flag of truce, she made her way north and settled in Paw Paw, Michigan. It was in Paw Paw where Malinda Russell published her cookbook in 1866.

In the page entitled “Rules and Regulations of the Kitchen,” she says, “I have made cooking my employment for the last twenty years, in the first families of Tennessee (my native place), Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky. . . Being compelled to leave the South on account of my Union principles, in the time of the Rebellion, and having been robbed of my hard-earned wages which I had saved; and as I am now advanced in years, with no other means of support than my own labor.”

The cookbook contains many recipes for sweets, reflecting her bakery background. The cookbook also shows the variety of foods that were eaten by people in those years, both in the North and in the South. Malinda Russell’s recipes were written for an accomplished cook and baker to follow, providing the lists of ingredients with general descriptions of the quantity.

The recipes do not contain time or temperature for the recipes, as she expected those following her instructions to know the general operation and nature of cooking. The cast-iron stove without gauges was in common use during that time.

The measurement details include notation of “do,” which confused consulted chefs until it was discovered to be an abbreviation of the word “ditto,” as in the same measurement as before.

Enterprising chefs are interpreting the 160-year-old recipes written by Russell and have posted their baking instructions on YouTube videos, such as the “Recipes Remade,” presented by the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

Malinda Russell, in her Rules and Regulations of the Kitchen, says, “I know my receipts are good, as they have always given satisfaction. I have been advised to have my Receipts published, as they are valuable, and every family has use for them.”

David Winship is a native of Bristol, Tennessee, and a former resident of Abingdon, Virginia, where Malinda Russell operated a laundering business. He is a retired public-school educator and currently operates the letterpress shop at King University in Bristol. He is a member of Winston-Salem Writers and Appalachian Community of Poets and Writers.